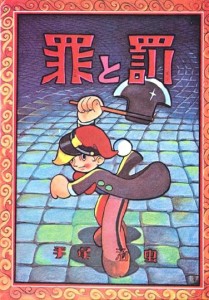

Crime and Punishment (Manga)

Also known as 罪と罰 (Tsumi to Batsu)

| English Title: | Crime and Punishment |

| In English? | Yes |

| Japanese Title: | 罪と罰 Tsumi to Batsu |

| Type: | Book |

| Original run: | 1953/11 |

| Published by: | Tokodo |

| Volumes: | 1 MT-010 |

One of Tezuka’s earliest attempts at adapting literary classics into manga, Crime and Punishment (1953) was originally published as a stand-alone book by Tokodo in November, 1953.

What it’s about

Set in St. Petersburg, during the final few days of Imperial Russia, a poor student named Raskolnikov pays a visit to a local pawnbroker looking to pawn his watch. Feeling that she has cheated him out of his rightful cash, he convinces himself that since she is a bad person she doesn’t deserve to live, kills her with an axe, and flees with her valuables.

When a poor, unwitting, but innocent man is charged with the crime, Raskolnikov believes he has literally gotten away with murder, and the elation of it leads him down the path of self-delusion. When he publishes an essay that suggests that people can be divided into either the “ordinary” or the “extraordinary”, and that those in the “extraordinary” category are above such things as right and wrong, it draws the suspicion of Judge Porfiry, the man assigned to investigate the pawnbroker’s murder.

Although he feels invincible at first, little by little, the guilt eats away at him, and, as Porfiry‘s investigation continues, Raskolnikov begins to feel cornered. When his sister Dunya sends him a letter, he realizes that she has become involved with Luzhin, a wealthy, but greedy man who wants Dunya as his subservient bride. While trying to help Dunya, he also becomes entangled with a poor family that also runs afoul of Luzhin, when the alcoholic father perishes suddenly in an accident and the daughter, the proverbial prostitute with a heart of gold, Sonya is left as the breadwinner in the family.

Becoming more and more entangled, Raskolnikov soon finds himself indebted to Svidrigailov, a shady character who helps Dunya escape Luzhin‘s clutches for his own motives, and eventually finds himself swept up in the chaos at the beginning of the Russian Revolution. Amidst the chaos, with Porfiry accusing him point-blank of murder, Raskolnikov can no longer stand the guilt and he confesses his crime to Sonya. However, to what consequence is that one act, set against the backdrop of a society in utter turmoil?

What you should know

Like Faust (1950), Pinocchio (1952), Cyrano, the Hero (1953), and Son-Goku the Monkey (1952-59), before it, Crime and Punishment (1953), is a somewhat ambitions attempt at adapting a literary classic into manga. Obviously distilling a work of several hundred pages, which deals primarily with the mental anguish and moral dilemmas, into a manga of roughly 130 pages aimed primarily at children is no easy task. As such, Tezuka’s version differs greatly from the Dostoevsky classic on which it is based. One of the largest changes is the inclusion of the Russian Revolution as part of the narrative context – an event which was still nearly 50 years away when the novel was first published. As such, Tezuka’s manga is much more open-ended, with the story simply fading away rather than coming to a finite conclusion. This, however, is something of a hallmark of Tezuka’s work. Rather than simply attempt to lecture his young readership, Tezuka preferred to point the way and let them come to their own conclusions. When taken in the context of the early 1950’s, one can truly appreciate the task of making high-minded concepts of morality palatable, informative, thought-provoking and ultimately entertaining to his young readership. One way to achieve this is to take many liberties with the original story, with Tezuka injecting, sometimes awkwardly, odd-ball bits of humour here and there.

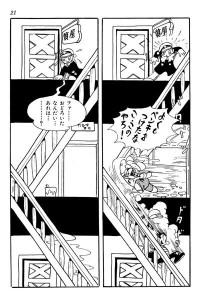

Stylistically, it incorporates much of Tezuka’s patented cinematic style. Clearly what stands out the most is the 11-page sequence where all the action takes place against a static view of the three-story walk-up. Tezuka nails his mental “camera” in place and lets the pawnbroker’s murder and surrounding events play out before it – we see characters rush up and down the stairs, and the easy banter of two men going about the business of painting the room below counterbalances the grisly, but silent, murder going on just above their heads. This juxtaposition heightens the dramatic tension to the point that, even though Tezuka conceals the actual murder itself, the reader feels an almost palpable need to call out the two oblivious painters. It should come as no surprise that Tezuka chose to highlight this sequence in a manner reminiscent of a stage production. In 1947, while still a student, Tezuka himself was cast as a painter in his school’s rendition of Crime and Punishment. Conquering his fear of heights, he bravely ascended to the top of a tall staircase built on-stage – only to find out later that all the audience could see were his feet!

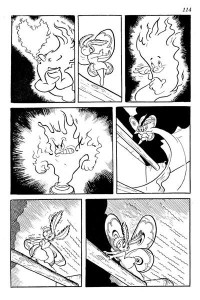

Also of note is the sublime sequence between Porfiry and Raskolnikov. Using the power of sequential art to its fullest, Tezuka punctuates Porfiry‘s speech about how he plans to draw the pawnbroker’s murder to him like a moth to a flame with a slow transition from the scene between the two men to one depicting an actual candle flame seducing a beautiful moth. The flame becomes more and more attractive, drawing the moth ever nearer, until finally the flame suddenly transforms back into Porfiry – making a memorable visual statement.

Finally, it should be noted that Crime and Punishment (1953) also marks a turning point in Osamu Tezuka’s career. It is the final book he would publish as part of his early career in Osaka. Spending more and more time working with Tokyo-based publishing companies, much of Crime and Punishment (1953) was completed while Tezuka commuted back and forth from Osaka to Tokyo.

Where you can get it

Luckily for English readers, the manga has also been released a few times. In 1990, shortly after Tezuka’s death, The Japan Times released a bilingual Japanese/English edition, featuring a translation by noted Tezuka expert, Fredrik L. Schodt. This edition has the distinction of being the first stand-alone Osamu Tezuka manga to be published in English (albeit in Japan!) and it is arguably the rarest and hardest of all his English manga to find. It’s so rare, in fact, many people do not even know this edition exists!

In North America, Crime and Punishment (1953) was first released in 2015 as part of DMP’s Digital Manga Guild initiative as as a digital-only release. It was available for legal download on the emanga.com website in a variety of popular reading formats (ePub, CBR/CBZ, PDF, etc.).

However (also in 2015) a print edition was also later successfully funded as part of the Kickstarter campaign to publish Storm Fairy in English. In total, 625 backers pledged $38,142 (of $14,200 goal) and, after the first stretch goals to not only reprint Uncio (at $26,000) but actually re-publish it using higher quality colouring (at $27,000) and paper were both met, the print edition (to replace the digital-only edition) was secured as the second stretch goal once the campaign reached the $32,500 mark.