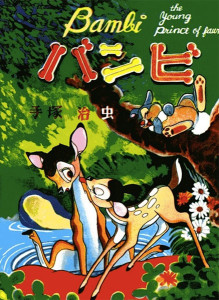

Bambi (Manga)

Also known as バンビ (Bambi)

| English Title: | Bambi |

| In English? | No |

| Japanese Title: | バンビ Bambi |

| Type: | Book |

| Original run: | 1951/11/10 |

| Published by: | Tsuru Shobo |

| Volumes: | 1 |

Osamu Tezuka’s Bambi (1951) was originally published on November 10, 1951 as a stand-alone book by Tsuru Shobo. It, like Pinocchio (1952), is a more-or-less direct adaptation of a Walt Disney classic animated feature film.

What it’s about

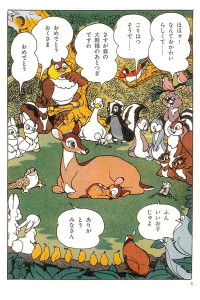

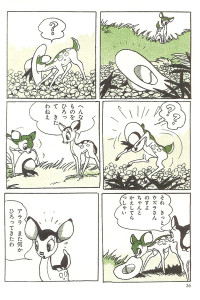

The story opens with the birth of the new prince of the forest, a young deer faun named Bambi. This causes great excitement, and all the animals come to pay their respects. After a bit of a wobbly start, the young prince is soon off to explore the world – with a little from his new friends, a rabbit and a beaver. As Bambi grows, his mother begins teaching him the way of the forest, especially in regards to the dangers presented by human beings. She also introduces Bambi to other deer, including a young doe named Faline. Although Bambi only meets his father by chance, it is a fortuitous meeting as the elder stag is able to drive off a pack of hungry wolves that have cornered his son.

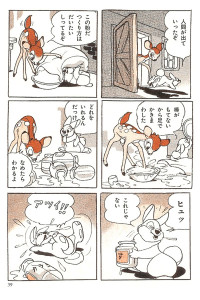

Soon enough spring and summer turn into fall and then winter. During the cold months, Bambi and his friend Thumper the rabbit stumble across a hunter’s cabin. Despite the danger, their curiosity gets the better of them and they quickly get into all sorts of mischief in the kitchen. Just as they steal a cake and set off for home, the hunter returns home and finds the animal tracks in the snow. So, with the hunter in hot pursuit and the bullets flying, Bambi’s mother tells her son to hide while she lures the hunter away from their den.

The plan works, but Bambi’s mother does not return and the young faun is left under the watchful eye of his father. As the seasons continue to turn, winter becomes spring and Bambi discovers he has newly grown horns. Of course, that’s not all he discovers. Faline has also grown considerably, and when she starts showing interest in Bambi, he is forced to battle a rival buck for her affections.

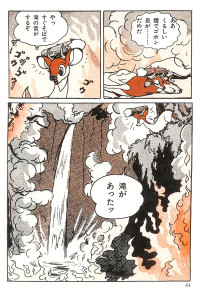

Although he is victorious, a hunter’s campfire soon starts a large forest fire and Bambi’s father is injured while trying to rally the animals to the safety of the river. In the aftermath of the fire, and with precious little to eat, Bambi is forced to fight off the hungry wolves to keep his friends and family safe.

However, when spring comes again, Bambi becomes the new Prince of the Forest and keeps a watchful eye over Faline and her two new baby fauns.

What you should know

To say Osamu Tezuka was a fan of Walt Disney’s works is something of an understatement. According to statements made by Tezuka himself, he saw Walt Disney’s Bambi (1942) over 80 times when it was first released in Japan in 1951. Impressive as that is, in a time before the advent of home video technology, many of those repeat viewings can probably be attributed to the fact that he was doing research for his own manga adaptation of the tale.

Given that his art style was already “Disneyesque”, it was a natural fit. Still, despite his familiarity with the source material, Tezuka allowed himself some artistic flexibility, and his adaptation deviates from the original animated motion picture in several ways. One example of this is are the changes to Bambi’s supporting cast – the Skunk known as “Flower” is partially replaced by a beaver, while a bullfrog more-or-less stands in for the wise old owl.

Furthermore, Tezuka’s version addresses one of the weaknesses (in his opinion) of the original story – the lack of interaction with man. Tezuka believed that animals with that level of self-awareness would certainly try to interact with human beings. So while Tezuka does keep true to the original by keeping all the human beings off-screen, he adds in a scene where Bambi and Thumper explore the human world via the hunter’s cabin. Of course, it’s interesting to note that he was exploring that same concept more fully via his own story, Jungle Emperor (1950-54) at the same time.

Also, probably conscious of his shonen-based readership, Tezuka ramps up the action and tones down the romance. So, while the battle between the rivals for Faline’s affections, the fight against the wolves, and the forest fire are particularly thrilling, Bambi’s interest in Faline as his mate is more subtle than the “twitterpation” he suffers in the animated version.

It also bears mentioning that, despite contrary comments elsewhere, Tezuka’s Bambi (1951) was officially licensed. However, as noted Tezuka scholar, Fred Schodt mentions in his book, The Astro Boy Essays, “copyrights were more loosely enforced in Japan than they are now” (2007, p. 44), so it’s understandable that Bambi (1951) is sometimes confused with Tezuka’s other adaptation of a Disney animated motion picture, Pinocchio (1952), which was not originally licensed.

In fact, Tezuka’s Bambi (1951) was licensed through an agreement with Disney’s agent in Japan at the time, Mr. Nagata Masaichi, the President of the Daiei Motion Picture Company – the company that was also responsible for distributing the animated motion picture at the time. As such, the Walt Disney copyright is clearly visible on the first page. However, it would take a more in-depth legal analysis to determine if Daiei Co. were actually within their rights to negotiate the manga license. It is most likely due to this uncertainty that neither Bambi (1951) nor (the certainly unlicensed) Pinocchio (1952) were included in the Osamu Tezuka Complete Manga Works edition that was released between 1977 and 1997.

Thankfully, Tezuka Productions and the Walt Disney Company have since reached a true licensing agreement and both works are now “legitimate” and have been beautifully reprinted in Japan.