Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 3: RESOLUTION

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 0: INTRODUCTION

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 1: CHILDHOOD

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 2: TRANSFORMATION

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 3: RESOLUTION

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 4: AFTERLIFE

Black Jack and Buddha (1972-1978)

Black Jack and Rock

Section 1: DISTRUST

We have now seen Rock at his worst, and also Tezuka at his worst, in the late sixties and early seventies when repeated conflicts with editors and publishers and apparent betrayals by friends seriously hurt his production studio and interfered with the publication of many series, including Phoenix and Vampires. Tezuka had fought loosing battles over control of his manga, and especially over his anime which he was never satisfied with as producers insisted on happier endings and watered-down political messages. Thus Tezuka was at his most depressed and pessimistic in the early seventies when he turned his attention to new projects.

From 1972 to 1983, Tezuka’s exploration of charismatic villains and the appeal of evil continued to manifest in many stories, from the violent social commentaries of Ayako (1972-73) and MW , to the more playful evil of Sharaku in The Three-Eyed One (1974-78), a charming boy who, with the removal of the bandage over his third eye, literally transforms from a sweet but childlike simpelton to a charismatic but terrifying evil demon. But Rock did not appear in these stories. Instead, Rock’s progression brought him into Tezuka’s two long-term projects of the period, two of his best-loved manga aimed at adult readers, the medical drama Black Jack (1973-83), and his biography of Buddha (1972-83).

Of the two, Buddha began serialization earlier, but because Rock did not appear until several volumes in, it is in Black Jack that we see his first real manifestations after Alabaster.

Section 2: DOCTOR AND PATIENT

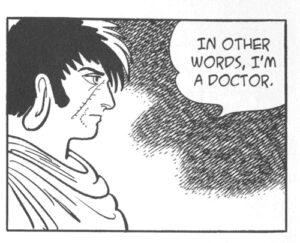

The solitary and brooding Doctor Black Jack is not only Tezuka’s most popular character in Japan, but the character with whom Tezuka himself most identified. The unlicensed surgeon’s refusal to respect any group or outside authority reflected not only Tezuka’s frustrations with the hypocrisy of the medical establishment as he had experienced it in medical school, but the frustrations with his own career in the publication and animation industry in which so many seemed to be against him. It may seem strange to claim that any particular character is an alter-ego for the author when the author appears as himself in so many of his own works, but if the character Osamu Tezuka is a reflection of Tezuka as he saw himself, then Black Jack can be said to be what Tezuka wished he could have been had he remained a doctor. Black Jack’s existence is impossible – no doctor in the real world could get away with bucking medical authorities like he does, and no one has the impossible skills which allow him to live so independently – but if the young medical student Osamu Tezuka had been strong enough and skilled enough to follow that impossible path, then he could have respected himself as a doctor.

Black Jack is such a strange and complicated character that Tezuka faced a great challenge in introducing him – how to get across Black Jack’s sinister outer persona, his impossible skill, his absolutist philosophy and his kind hidden nature in one short issue, and how to make the reader realize that this is not just another new character but the arrival of someone especially precious to Tezuka, and who would soon be precious to all of Japan.

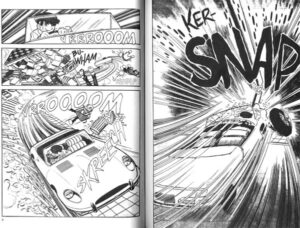

Spolied Rich Boy, Akudo

So, in issue 1, “Where’s a Doctor?” (11/19/1973; issue 1 of the Viz English release) Tezuka presents a story of a spoiled rich boy, Akudo, who is critically injured due to his own reckless driving, and whose rich bully of a father (Duke Red) tries, through bribery and threats against any who fail, to force the medical community to save his son. Only the sinister Dr. Black Jack rises to the occasion, offering save the boy if Duke Red provides him with a complete body. Duke Red has an innocent boy sentenced to death to have Black Jack take his organs, and after many hours of surgery Black Jack claims to have saved Akudo, while in fact he has simply performed plastic surgery on the innocent boy to make him look like Akudo so Duke Red would think his son was saved and not hurt anyone. Black Jack then gives the operation fee to the boy and his mother so they can flee the country. When asked why he did not save Akudo, he answers that Akudo’s body and soul were both rotten to the core, so there was no point in trying.

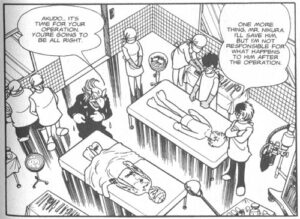

Black Jack performs the operation

There is perhaps no better example than this of how Tezuka’s different works take on new meaning when read together. Taken by itself, the story is extremely unsettling as we see Black Jack abandon a patient based on his own judgment that the boy is not worth saving, and perform a strange transformation on another unrelated boy. But Akudo is the very same Rock whom Tezuka’s readers had watched degenerate from a broadminded but selfish boy detected to a charismatic villain to the unforgivable monster FBI, and as we see his mutilated body lying on the operating slab it seems like a just destruction of the beauty FBI so prided himself upon.

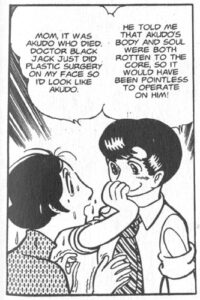

Brand New Akudo

By seeing at a glance that Rock is rotten to the core, Black Jack demonstrates profound wisdom and discernment, letting the Tezuka reader know that this is a man who understands the Tezuka universe perfectly, and whose judgment should be trusted as absolutely as his skill. That he solves the problem by transforming another good and innocent boy into Rock connects the story to Rock’s abilities of disguise and transformation. The characters themselves rejoice that Black Jack has performed a “miracle” in saving them from Duke Red, but the true miracle is in having destroyed the evil Rock and recreated the kind, light, young Rock of Detective Boy Rock Holmes whom Tezuka’s readers had loved and missed for the years he had spent as a villain. If Black Jack can heal even Rock’s transformation, then his powers of healing are, in a metaphysical sense, greater even than the Phoenix’s.

Rock’s appearances in Black Jack cluster, with five and a cameo from 1973-1975, followed by a long gap, and three more issues in 1978. Two of the appear in the last ten issues of the original continuous run of Black Jack, as Tezuka felt himself to be winding down the story of this most precious character. During the gap, from 1975 to 1978, Rock appeared in five other series, and most critically in Buddha, but for several years after Akudo’s first death Rock appeared exclusively in Black Jack, whose episodic nature let Tezuka explore multiple incarnations of his Transforming One in rapid succession, much as he had done with the reincarnations in the second section of Vampires.

In issue # 5 “Man Bird” Tezuka could not pass up the chance to give Rock a cameo as a spectator watching Black Jack’s bird-woman creation fly, just like his friends Epoom bird race, and as he had done himself in Nextworld, but Rock’s next serious appearances are in issue 11 “Nadare the Deer,” issue 57, “Black Queen,” and most important in the sealed issue #28, “Print Proof.”

Nadare the Deer

In “Nadare the Deer,” Rock plays the young Nobel prize candidate Dr. Ohedo, Rock has been researching techniques to remove the limits on development of the mind by having Black Jack experiment on his beloved pet deer Nadare to expand its brain, granting it human-level intelligence which implies that the same operation, if repeated on a human, could grant intellectual powers far beyond what nature and the universe intended. Rock’s experiment backfires as Nadare, seeing the horrendous environmental destruction mankind is inflicting upon the kingdom of nature, declares himself the defender of the forest and attacks and kills invading humans. Black Jack helps Rock kill the creature, with a sense more of “I told you so,” than of sympathy as he watches Rock collapse in tears.

Locked and Loaded

In this case Rock is again his less-evil self, with the interests of humanity in mind as well as his own, but the appearance of his characteristic sinister sunglasses gives us an unsettling idea of what he use would have found for intelligence-increasing technique had he gotten as far as testing it on himself, or other humans. Of course, had any other mad scientist in fiction attempted the same experiment we would have expected his creation to turn on him in the same way, but in this case the King of Transforming Creatures is trying to transform an animal into a human, just as he did with the Ueko in Vampires, and the reverse of the ZZZ gas which brings peace to humans by reducing their minds to animal level. Rock is continuing the same project as in previous lives, but in this case he is also trying to rebel against the order of nature by forcing life forward instead of back, a progression which is not his role in the universe, and is consequently crushed.

Rock shoots Nadare

Not infrequently when Black Jack was reprinted in collections after its initial serialization, Tezuka would order certain issues to be withheld from the reprint. Often they would be issues which had been criticized by the medical community, or which had upset patients suffering from the illnesses depicted, which bothered Tezuka greatly. Occasionally, though, as in the case of issue #28, Tezuka would have a story excluded from the collection because he himself was simply unsatisfied with it, and at his request #28, “Finger” has never been reprinted in any collection or translation since its initial magazine publication on June 24th 1974. Instead, Tezuka would continue to think about and work on this issue for the next four years, and eventually re-write it as the third-to-last issue of the original Black Jack series, #227, “Print Proof.”

Rock and the Black Queen

Both versions of the story deal with Rock and Black Jack as having been childhood friends, orphans growing up together, sharing their dreams and ambitions as they struggled toward adulthood. As Black Jack became a doctor, following his mentor Dr. Honma (Phoenix‘s Saruta), the sweet boy Rock set out to seek his fortune, becoming the dark criminal mastermind Makube Rokuro, just as we knew him in Vampires. In the original story, Rock calls on Black Jack to ask (or force) him to perform a operation to change Rock’s fingerprints, the one part of his body he can’t transform on his own, to help him evade the police. Black Jack performs the operation, but Rock betrays him and tries to kill him afterwards. This grim and wicked portrait of Rock as friend and traitor came at what was, for Tezuka, one of the bitterest times of his life when he felt betrayed by those around him, so his strong self-identification with Black Jack suggests that this grim ending was a reflection of his real-life disillusionment.

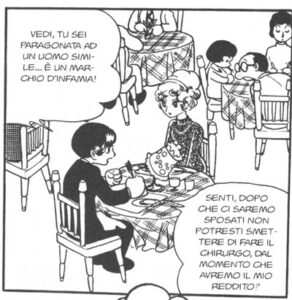

Rock appeared twice in Black Jack before his three-year hiatus. The first was issue #57, “Black Queen,” in which he plays the fiancé of a dark and icy lady doctor (Zephyrus from Unico). Rock and his fiancé have a fight (with Tezuka himself eavesdropping in the background) becuase her sinister reputation threatens to damage the rise of his career. She is tempted to leave Rock for Black Jack, whose lifestyle is closer to her own, and Black Jack demonstrates clear romantic interest in her but ultimately helps her to stay with Rock.

This story would be revisited three years later in issue #199, “The Last Train,” in which Black Jack again encounters the Black Queen, now Rock’s wife, and again rejects her romantic advances and conspires to force her to stay with her husband. In both these cases Rock and Black Jack never meet, but by making them rivals in love appealing to the same woman, Tezuka sets up another comparison between them, since first they were two friends who grew up together, and now two men similar enough to be interested in (and appealing to) the same beautiful, cold, ice-queen.

Rock: Political Activist and Terrorist

The last of Rock’s early Black Jack appearances, issue #83, “Rats in a Sewer,” shows an even more strictly dark Rock and an even more morally superior Black Jack, as Rock plays BB, a young political activist and terrorist leader, the son of a wealthy father whom we never see but must assume to be Duke Red.

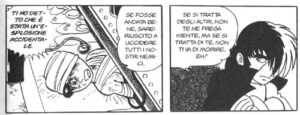

Rock Trapped!

BB is gravely injured by his own bomb, and his men kidnap Black Jack and force him to save Rock. Black Jack does, but leaves the horrifically maimed BB in the care of the residents of the building which he was going to destroy. The story concludes with Black Jack moralizing at BB about the hypocrisy of using violence to achieve one’s goals, which serves as a reminder that, whileBlack Jack does not shrink from killing to defend himself or his loved ones, he does not share Rock’s acceptance of violence as an acceptable means of achieving good.

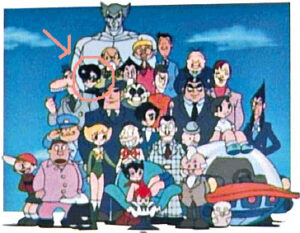

Rock in Jetter Mars

After this, Rock took a hiatus from Black Jack to befriend and try to civilize a wild man in The Story of Stone (1975), to transform into a werewolf himself and die fighting a transformed monster in Metamorphosis “Woobit” (1976), and to have one more sci-fi gambit in The Story of Bis Bis Bis Planet (1975). He was also intended to encounter astro again in the Jetter Mars TV series (1977), a new version of Astro Boy with his name changed for copyright reasons, in which Rock would no longer be a classmate or boy detective but his villainous mature self – unfortunately Rock was cut from the final production, but still appears in the cast shot in the credits, dressed all in black with the usual dark sunglasses which mark his darker roles.

But the truly vital progress of the reincarnation cycle, not only for Rock but for many of Tezuka’s characters, lay in the companion piece to Phoenix in which, for one lifetime, reincarnated souls have the opportunity to break the patterns of their lives as they meet the Buddha.

Section 3: THE ENLIGHTENED ONE

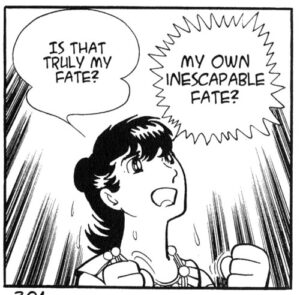

Can Rock escape his fate?

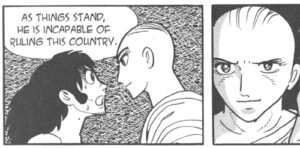

Unlike most of Tezuka’s earlier works of fiction, Buddha is a biography, based to a certain extent upon the historical tradition about Buddha’s life, but Tezuka exercises his creativity in how he links and fills the gaps in the story, and in how he chooses to cast his stars into the traditional narrative. Rock he casts as king Bimbisara of Magadha. Bimbisara is a wise and confident young king, and receives from the young sage Assaji the prophecy that in twenty years he will be killed by his own son, who will then also receive punishment for the sin. After testing Assaji and proving that his prophetic powers are true, Bimbisara is plagued by the prophecy for the rest of his life.

King Bimbisara maintains his dignity in public, but in private laments his fate, not as much for himself as for the death of his ambitions; he has been a fair and just ruler, made his kingdom wealthy and powerful, the envy of his neighbors, but he has many goals remaining, and “what can I achieve in two measly decades?” After all, Rock has always been ambitious, both in his light, exploratory roles and in his darker power-hungry personas, and now that he is finally king (as the weird sisters prophesied years earlier in Vampires) he faces the inevitability of his own death, and the extremely limited scope of what he can accomplish even in a lifetime of success and power.

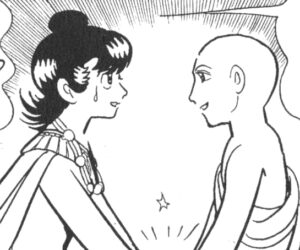

Bimbisara and Siddhartha

When Bimbisara first lays eyes on Siddhartha, he immediately recognizes his noble bearing and kingly features, and begs Siddhartha to join him as a general or noble advisor, considering Siddhartha’s ascetic path a waste. When Siddhartha refuses, Bimbisara asks if Siddhartha will at least be his spiritual advisor, and help him prepare for the foreordained which looms over him. Siddhartha agrees, and the two embrace as friends, at which point it is Bimbisara who gives Siddhartha the name Buddha, “Enlightened One.”

Here Bimbisara’s, or rather Rock’s, ability to instantly recognize the greatness in Siddhartha when so many others doubt him is comparable to Black Jack’s ability to spot Rock’s rottenness in their first encounter in Black Jack issue #1, but his focus on power and kingship make him value Siddhartha’s royal and military potential above his theological potential. Only later, as he faces his oncoming death, does Rock realize how much more valuable spiritual guidance is than political power, which also means admitting the futility of all his lives’ ambitious schemes.

Rock’s Fate

King Bimbisara grows old over the course of Buddha, growing almost unrecognizable to an audience who has never before seen Rock as anything but a youth. Ironically, we have seen Rock die many times as a schoolboy or young man, and here, the one time we see Rock survive into middle age, he spends his two precious decades lamenting the shortness of a life he does not realize is much longer than he usually gets.

Buddha is a story of exceptions, for everyone, not just Rock. Saruta was sentenced by the Phoenix to spend all his reincarnations ugly and isolated, suffering as he pursues an understanding of life and the universe which he will never quite achieve. In Buddha, he is permitted to give up science for one lifetime and follow Buddha to a peaceful and spiritually contented life. Sharaku is another of Tezuka’s great transformers, the The Three-Eyed One who, in his own series, can switch, with the unsealing of his third eye, from an imbecilic, infantile good-hearted but impish boy to an all-powerful evil genius bent on dominating and destroying humanity. While in The Three-Eyed One the focus is always on demon Sharaku and the appeal of his evil charisma, here as Assaji he is allowed to remain permanently in his good-but-infantile human form, and for once others recognize the sage-like wisdom of his calm kindness and simplicity.

The miraculous healer

These long-suffering characters are, just this once, saved, as are many others, by the presence of Buddhism’s message of inner peace and spiritual healing, with people achieve personal happiness even when they are doomed to lives of suffering. The fates decreed to Saruta, Sharaku, and others, by the cycle of reincarnation governed by the Phoenix are not rescinded, but through Buddha’s presence their inner selves are saved nevertheless. Buddha is a doctor of the soul, healing the internal wounds which medicine cannot touch, and to make the comparison clear Tezuka has Buddha appear as Black Jack for one panel. Buddha and Black Jack become the same figure in this sense, the miraculous healer, one who follows his own path despite the pressures of society, a figure Tezuka wishes he could be.

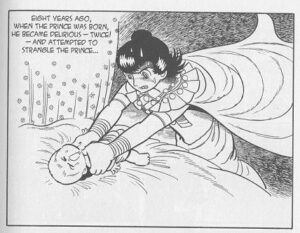

Is Devadatta really Yuki?

But Rock is not saved. Bimbisara is twisted by the prophecy and becomes frightened of his own son, has him imprisoned and tormented, and murders his first love. His son then, scheming with the wicked and ambitious Devadatta (who bears a striking resemblance to Yuki from MW) has his father imprisoned and starves him slowly over a course of years. Thus Bimbisara is jointly destroyed by his own willingness to turn his back on his son, a sin enabled by Rock’s perennial willingness to abandon love and friendship, and by Devadatta/Yuki, Rock’s successor as the worst monster in the Tezuka corpus.

If Devadatta is indeed Yuki, the monster one step worse than the worst Rock can become, then his fate in Buddha must be contrasted with Rock’s. King Bimbisara becomes rotten and tries to destroy his son, but he always accepts and respects Buddha and attempts to follow him. Ambitious as Rock always is, he is content to follow and learn from Buddha, and remains loyal to him despite his characteristic ability to cut off friendships. Devadatta, meanwhile, hates and envies Buddha’s greatness, and tries to overthrow and ultimately kill Buddha because, he says, “I could not be you.” As Devadatta is destroyed by his own attempts to kill Buddha, Buddha pronounces sadly that Devadatta was his own worst enemy. Rock’s worst enemy is his fate, that is the universe itself.

A wretched end for Rock

Rock at the end of Buddha as wretched as we have ever seen him, sick, frail and ugly, deprived of the beauty which was his pride in Alabaster, imprisoned without human contact just as when he was broken in Nextworld and turned dark for the first time. Yet Rock does not, like Assaji, accept his death calmly, but clings desperately to life, having his wife smuggle honey in to him on her skin, not enough food to save him but only to extend the period of his suffering. Buddha fails him as a spiritual advisor, and does not keep the first promise he made, to help him prepare to face his death.

This failure comes at the end of a series of failures which had left Buddha in doubt about his own spiritual message, as he watched so many of his own people and own closest followers die and his sect fall into disorder, while he himself seems increasingly unable to change people. The death without salvation of Bimbisara, one of Buddha’s oldest and most loyal followers and the first to recognize him as “the Englightened One,” is the final proof that even a follower who is wise, willing and patient sometimes cannot be saved. But as Buddha fails to save Bimbisara, Bimbisara in turn saves Buddha by making a request that will lead Buddha to the final great spiritual revelation of his life.

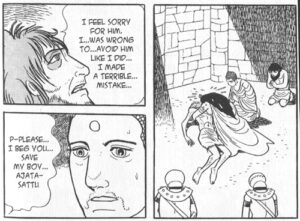

One final request

Bimbisara wants Buddha to save his killer, his son Ajatasattu, who is suffering from an illness which is the physical manifestation of the wickedness which has infected him due to his father’s maltreatment, enabled by Devadatta’s manipulation. Buddha diagnoses the condition as stemming from the young king’s isolation, again reminiscent of the solitary confinement which broke Rock in Nextworld, and slowly, methodically heals him through his simple presence and human contact. When he sees the recovering Ajatasattu’s smile, Buddha realizes at last that the divine exists within the human, that all people are capable of change and that Buddhism does not have to be an exclusive path for ascetics and monks but a philosophy for all people. All life is sacred, he preaches, and at times you must suffer, or even sacrifice yourself to save another, but the greatest gift is to help others, even if just by showing sympathy for one who suffers.

The healing touch

Buddha cannot save Rock because he cannot change Rock’s fundamental nature. He is The Changing One. He is ambitious and selfish, and will decay into darkness over his lifetime while struggling to maintain his power and himself. But Buddha did give Rock sympathy in his suffering despite his sins, and thanks to Rock, Buddha has learned that this is the most powerful gift which it is in a human’s power to give. Rock has suffered and will suffer the same way in many lifetimes, from Detective Boy Rock Holmes to the end of humanity in Phoenix “Future,” but unlike his solitary deaths in Phoenix, Vampires and Alabaster in Buddha he has others to mourn him and sympathize with his suffering. Rock, in turn, gives sympathy – and, though Buddha, salvation – to his son whom he realized he had caused to suffer.

Buddha’s lesson to Rock, then, is that Rock deserves to suffer and to die…

Rock’s last request is that Buddha save his son from the damage done by Devadatta/Yuki and by Rock himself, but his second-to-last request is that his wife not hate their son, because in suffering at his son’s hands, Rock says, “I only got what I deserved.” We have never heard these words from Rock before. Bimbisara who became wicked and imprisoned his son may deserve punishment, but so too does Rock Holmes who turned time and again to darkness, FBI who committed rape and murder, Makube Rokuro who tried to overthrow civilization and kill his own creator, BB the terrorist, Akudo who was rotten to the core, and Rock from Phoenix “Future” who abandoned humanity to save himself in the face of war. But until Buddha he never accepted it. Buddha may not have alleviated Rock’s sufferings at all, but his gift to Rock is the revelation that the Transforming One, the one who turns to darkness, cannot and should not be saved.

Buddha’s lesson to Rock, then, is that Rock deserves to suffer and to die. Rock’s lesson to Buddha is the same, that some people deserve to suffer and die and cannot be saved, a lesson which the semi-Buddha Black Jack certainly remembered in issue #1 when he left Akudo to die. If Rock’s position in the universe, is as a living lesson that not all can be saved, that some dark transformations are irredeemable, then his laughter as he waits for death in Phoenix “Future,” takes on new meaning. It is no longer madness, but the confident, ironic laugh of a creature who knows that it is his purpose to prove to the Buddha – to the universe in general –that the creatures within it suffer because it made them to suffer, as it made Rock to degenerate and deserve death, and that, seeing him, Buddha and Phoenix alike must admit that the universe itself decided to contain suffering when it decided to make some people Rock instead of Kenichi, and to make some races human instead of moopies.

Rock’s civilization in Phoenix, a civilization which had abandoned Astro’s dreams of universal friendship and exploration and become nostalgic, backwards-looking and lifeless, deserves to be wiped out and replaced. But it is not fair that it deserves it, because the universe utself, by creating moopies, and by creating man with a capacity for Nostalgia, effectively designed humanity so that it would inevitably degenerate and deserve death. In the same way, it is not fair that Rock must suffer and die in every lifetime because the universe created him with the capacity to choose evil and to change. The universe made man, and Rock, capable of transformation, and of suffering, by giving humans a conscience while also making them capable of recognizing the utility of evil– if men were beasts, they could do evil without regret or taint, and suffer without understanding, as both the Vampires and ZZZ wished to enable. But the Phoenix did not allow this, and Rock, and humanity, deserve to suffer. A perfect Buddha, then, cannot coexist with the realities of such a guilty universe, not unless he becomes willing, like Black Jack, to admit that sometimes individual people, or even whole nations, are too rotten to be saved, and that it is the universe’s fault.

Section 4: Acceptance

If in Vampires Rock seems to retain the revelation from Phoenix that there is reincarnation, that he has lived before and will live again through the same cycle of change, degeneration and death without sympathy by the Phoenix who controls his fate, so too after Buddha he retains the new lesson that he deserves what he gets.

Rock – Black Jack BFF!

In Black Jack issue #199 the Black Queen returns and once again offers to leave Rock for Black Jack, while in issue #221 “Tenacious Black Jack,” the two literally enter into a competition to see who can be more stubborn, in which Rock, as the novelist Homura Rokuhisa, ultimately looses. Finally, in issue #227, as the run of Black Jack was finally drawing to a close, Tezuka finally chose to revisit and repair the story of Rock and Black Jack’s childhood friendship from the sealed issue #28, which he had never been satisfied with.

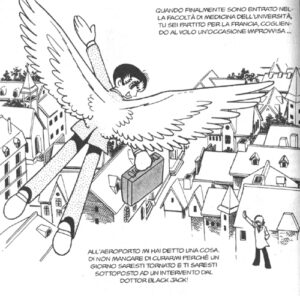

Rock takes flight

Here we see the young Rock and Tezuka’s idealized alter-ego Black Jack together as children, sharing their dreams for the future. Black Jack tells Rock he wants to become a doctor, and Rock, with the same insightfulness with which he identified Buddha as the “Enlightened one” prophesies that Black Jack will become the worst doctor in the world, “because you’ll have Dr. Honma’s skill and my personality.” We also see Black Jack bidding farewell as Rock sets off to seek his fortune, flying away to foreign parts, not in an airplane but with wings reminiscent again of his flight in Nextworld and his Epoom bird people, but also resembling the wings of the Phoenix herself, who is bearing him off once again to face the destiny he can never escape.

Rock returns evil, as is inevitable, especially since Tezuka has specified that this is not just any version of Rock but Makube Rokuro, the Rock from Vampires, the first evil Rock whose end we never saw, since Vampires remained unfinished. Now Makube has become nearly blind from surgery intended to transform his eyes from one color to another, the same eyes with which he exerted supernatural control over vampires and ueko. But Makube is not interested in having Black Jack heal his eyes – he doesn’t need them. Makube only wants Black Jack to replace his fingerprints, so the police cannot identify him. Black Jack is given no choice in the matter, but held hostage until the operation is complete, then released and paid, but a bomb concealed in the case of money nearly kills him.

Later, a confident Makube sits at police headquarters gloating that they cannot prove his identity, when a fax from Black Jack reveals all, describing the operation and offering as proof the initials BJ which Black Jack carved into Makube’s finger bone during the operation as insurance against betrayal, showing that he, just like Rock, has a personality which does not trust, and always prepares to betray. Makube is sentenced to death for his crimes – it is not necessary to specify what crimes since we all remember the list of sins for which he never paid in the unfinished Vampires– and Black Jack visits him on death row, to ask whether it was Makube who ordered the bomb be placed in the money or whether his men did it. Makube denies it, but Black Jack does not believe him until he removes his characteristic sinister sunglasses, returning to the character design of his more innocent, pre-Vampires self. Realizing the truth, Black Jack says he is sorry about Rock’s inevitable execution, but Rock answers, as calmly as in Buddha, “No, it’s okay.”

Later, a confident Makube sits at police headquarters gloating that they cannot prove his identity, when a fax from Black Jack reveals all, describing the operation and offering as proof the initials BJ which Black Jack carved into Makube’s finger bone during the operation as insurance against betrayal, showing that he, just like Rock, has a personality which does not trust, and always prepares to betray. Makube is sentenced to death for his crimes – it is not necessary to specify what crimes since we all remember the list of sins for which he never paid in the unfinished Vampires– and Black Jack visits him on death row, to ask whether it was Makube who ordered the bomb be placed in the money or whether his men did it. Makube denies it, but Black Jack does not believe him until he removes his characteristic sinister sunglasses, returning to the character design of his more innocent, pre-Vampires self. Realizing the truth, Black Jack says he is sorry about Rock’s inevitable execution, but Rock answers, as calmly as in Buddha, “No, it’s okay.”

Friendship redeemed

In this revision, four years after the initial version in which Rock did betray Black Jack, Tezuka’s view of Rock, and of the world in general, has lightened, and he writes a Makube who retains the principle of friendship despite his transformation. Black Jack, Tezuka’s alter-ego, does have Rock’s personality, dark, hardened by suffering, willing to pursue dark means to good ends, willing to do wrong and be thought evil. Also as Rock said, he has Dr. Honma’s skill, not just as Honma the doctor but Saruta, the closest thing to a protagonist in Phoenix, who quests unceasingly to understand life and death and the order of the universe. And Black Jack too is the Buddha, or at least a limited Buddha, committed to healing, if not all humanity’s wounds, at least every soul he can reach in his limited lifespan.

By retaining his friendship with Black Jack, Makube here proves that Rock’s transformation has limits, that he has not completely renounced human morality and goals. Rock will not, as his worse counterpart Yuki/Devadatta did, try to kill Buddha/Black Jack. He still has remnants of the detective boy who could work alongside Astro and Kenichi, and is capable of being as loyal a friend as they are, at least in this case where Black Jack is at once friend, his better reflection, his savior, his destroyer, and his creator. By remaining true to Black Jack Makube has, in a sense, made up for trying to kill Tezuka so many years before, or Tezuka has concluded that Makube would not try to kill Tezuka’s more perfect self, which Black Jack – almost a Buddha – represents.

Previous: Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 2: TRANSFORMATION

Leave a Reply