Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 2: TRANSFORMATION

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 0: INTRODUCTION

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 1: CHILDHOOD

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 2: TRANSFORMATION

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 3: RESOLUTION

Rock Holmes: Transformation – Part 4: AFTERLIFE

Rock in Vampires

Makube Rokuro (1966-1971)

While almost all of Tezuka’s recurring characters continued to play the same types of roles in all their appearances from beginning to end, Rock underwent a unique and definitive transformation in 1966, which divided not only his career but Tezuka’s in half. Vampires (available in French), serialized from 1966 to 1969 was an entirely new kind of story for Tezuka in which he took as his subject the innate animal desire to do evil which, he believed, lives stifled inside all human beings. This was a stark break from his earlier good hero vs. villain stories, as for the first time he presented evil in an appealing light.

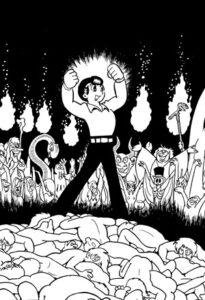

Vampires is, just like the others, a story of two races coming into conflict, here humans and the Vampires, but the “vampires” in Vampires seem very alien to the standard definition of a vampire. They do not drink blood, are not immortal, are not confined to night time, indeed do not have any of the characteristic traits of a vampire, but are simply people who transform into beasts – werewolves, or in some cases were-snakes, were-bats, were-goats, were-alligators or a variety of other creatures. They are called vampires, though, because they can prey upon humans, not for blood, but for anything they want, from meat to money. Because these transforming creatures have the minds of animals, they are free from the human constraints of conscience and morality and can pray on men, and on one another, as freely as wild beasts.

Long ago, the story claims, all humans were, like other animals, without conscience, but as civilization developed man became restrained by morality. The vampires seek to free mankind from morality’s restraints by overthrowing civilization and making man an animal again. This plot is, in effect, a darker retelling of ZZZ’s scheme in Astro Boy to bring about world peace by regressing world leaders into animals, and indeed even the ZZZ mind-regressing gas features in the story. The vampires seek to end civilization and initiate a Hobbesian war of all against all because that is their concept of freedom, but their universal war would also mean an end to the worse horrors of organized, global war and to the threat of technological annihilation.

Dark Rock

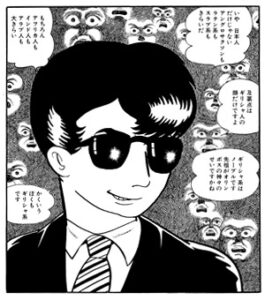

As the leader and primary villain of this first exploration of the appeal of evil, Tezuka presents, not a twisted or comedic villain like Skunk, Lamp or Ham Egg, but the charming, charismatic Makube Rokuro, “Ma-ku-be” a pronunciation of Macbeth, and Rokuro, a common Japanese name which takes on new meaning hear as we read it as Rock + “kuro” meaning “black,” so literally “Macbeth Dark-Rock.” Naturally, he goes by the nickname ‘Rock’.

Makube is still a schoolboy, the same age as in Nextworld or Adventures of Rock, but here he is a vicious criminal genius, engaged in a complicated and boldly-staged plan to infiltrate and murder a wealthy family in order to take their fortune for himself. His face and hair are the same, his body type similar, though somewhat less childlike as Tezuka’s entire art style becomes more refined. And here at last we see Rock begin to wear the characteristic dark sunglasses which will be his signature in so many later stories.

Makube is no timid villain. The rap sheet for his first criminal role includes kidnapping, extortion, murder, terrorism, torture, theft, hijacking, and organizing mass riots, assassinations, looting and revolution. As for Makube’s criminal skills, he is patient, methodical, quickly adaptable and able to exploit any new opportunity presented. He is also a master of disguise, a characteristic he will retain in many later series, donning an infinite variety of faces, old and young, male and female, in order to pursue his goals. Those who met Rock for the first time in the Metropolis movie may have been taken totally by surprise by his use of disguise in the film, since there is no mention of it before its dramatic revelation, but any reader familiar with Rock would have recognized it as skill he has possessed continuously for forty years. It is also in Vampires that Rock’s handsome and youthful appearance are for the firs time made to seem effeminate as he dons female guise, an effeminacy which will be exaggerated and exploited more by Tezuka in even more vicious versions of Rock.

In some sense, this villain Rock can be seen as the natural extension of the boy detective who was able to recognize the practicality of violence and evil in achieving one’s goals, but while Rock Holmes always pursued peace, exploration and other goals shared by Kenichi, Astro and other boy heroes, Makube Rokuro employs the tools of evil only for himself. He is not, like the vampires, trying to liberate mankind from a moral system he sees as oppressive, but is rather a power-hungry criminal led, like Macbeth, by a prophecy given by three weird sisters who tell him he will be king.

Section 2: THE TRANSFORMING ONE

Evil is part of nature, a part of all humans, useful in the natural conflict between races, and any attempt to reject Rock’s path and emulate Kenichi and Astro is an unnatural, difficult, and human choice.

Though he and the vampires advocated freedom, even Makube is not entirely free from friendship, or from conscience. Repeatedly throughout Vampires he finds himself unable to kill friends when he wants to, or having to force others to finish off one of his victims for him while he flinches. Yet at other times he kills without restraint. This apparent fluctuation of conscience is clearly a remnant of Rock’s former, non-villainous persona. In Vampires, though, it also has a very specific meaning as it is suggested many times that Makube himself may be a vampire. Other vampires who encounter Makube sense instinctively that he is a vampire, and even go so far as to kidnap him and torture him (gently) to try to get him to transform. His seemingly-supernatural ability to command other vampires makes it almost certain he is one of them, but despite the vampires efforts, he never visibly transforms. My own interpretation is that Makube is indeed a vampire, but that he transforms into the animal ‘human,’ that is a pre-civilized, conscience-less human, the kind the vampires are trying to recreate in their revolution. Thus, in the moments when Makube is a ruthless killer, he has transformed into a beast man, a pre-civilized man, while when his conscience suddenly returns he has reverted to an ordinary, guilt-ridden human. His transformation is real, but physically in detectible, manifest only in the expansion of his capacity to choose evil. The vampires, then, obey Makube instinctively because he is the king of vampires, as man is the king of beasts. Makube’s ability to disguise himself as other humans can then be seen as another hint at his status as a transforming creature, one who transforms into many humans, while his personal transformation is invisible.

Taken in the larger context of Rock’s appearances up until this point, Makube’s ability to transform into a non-civilized human is an exaggerated version of the boy Rock’s unique tendency to accept the utility of lying, treachery and violence, and to reject friendship when it will only lead to suffering. Makube embodies everything which made Rock different from Kenichi, and shows us even more clearly why Kenichi’s path is heroic, while Rock’s pragmatic but selfish pessimism leads to a far more sinister road. At the same time, by associating evil and amoral behavior with animals and the pre-civilized state of man, Tezuka refuses to make any pretense of arguing that evil is wholly bad or unnatural. Evil is part of nature, a part of all humans, useful in the natural conflict between races, and any attempt to reject Rock’s path and emulate Kenichi and Astro is an unnatural, difficult, and human choice. This makes Rock’s transformation from hero to villain less a matter of progression from early works to late than a constant character trait – Rock is the transforming one, while Kenichi is the constant hero, and Astro, perhaps, the explorer, a hero who learns but does not change.

It was also in Vampires that Rock first met his maker, the famous manga artist Osamu Tezuka, appearing as a major character in his own story for the first time. Initially Rock discovers that Tezuka is taking care of the young vampire Toppei and blackmails him, and as Tezuka attempts to defend Toppei, Rock goes so far as to attempt to kill him. As the situation worsens it is Tezuka who organizes the forces to oppose Rock’s attempted world coup. Rock thus achieves a unique degree of villainy having tried to blackmail and murder Osamu Tezuka himself, but Tezuka as author also achieves a unique degree of honesty in personally appearing to oppose his own charismatic but evil creation. We the readers are tempted to sympathize with Makube, but the author personally steps in to remind us that evil is evil, however charismatic.

But Tezuka is not Astro or Kenichi, and he cannot realistically oppose Rock without making some dark choices, just as Rock would. To save humanity, Tezuka himself resorts to blackmail, to extortion, to violence, and ultimately to using the same evil gas ZZZ tried to use against Rock and Astro Boy years before. Here we see one of the first cases of Tezuka using the trick of author as character to take extra responsibility for a questionable choice. In the upcoming years, Tezuka will appear from time to time as a doctor in Black Jack in order to personally deliver diagnoses of the cruelest and most unfair illnesses, literally taking responsibility for the doom he has selected for his characters. At other times, Tezuka will insert himself in a character’s place for one panel, often to accept the repercussions for an objectionable line which he put in the character’s mouth. In Vampires, Tezuka the author has resorted to having his characters use lesser evil to defeat a greater, but by wielding the questionable weapon with his own hands he makes it clear that he is not trying to pretend that good has triumphed. Makube never comes to know that Tezuka is actually his creator and complain in person about his fate (that distinction will be reserved for the long-suffering Rainbow Parakeet), but he does have the distinction of having forced Tezuka to accept his own darker methods, by which Tezuka effectively admits that the lighter models of Kenichi and Astro are impossible.

Makube dies at the end of the first half of Vampires (1967), not at Tezuka’s hands but at his own, leaping into the sea to flee the ghosts of his victims who haunt him (death by drowning fulfilling the prophecy that he will not be killed by man or beast). Strangely, though, as he drifts out into the sea, Makube is calm, no longer pursued by the specters nor struggling to survive, but declaring with blank confidence that he will be back and continue his attempts to rule. This is very different from the selfish young man determined to survive whom we saw in Astro Boy and Nextworld. It is possible to interpret Makube’s death here as an ordinary fake villain death, that he didn’t really die but it just looked like he did. But another interpretation is that Rock, after so many incarnations battling the same kind of enemies and pursuing the same goals, is in some dim sense aware of his own reincarnation, and knows he will return to fight the same battles again, both in the second half of Vampires two years later and in other works in the Tezuka corpus. After all, 1967 was also the year Tezuka published Phoenix “Dawn,” the first key volume of the reincarnation cycle which would remain the core of all his works for more than twenty years.

Section 3: REINCARNATION

“All things are born and all things die; this is the universal law.” In Phoenix: “Dawn,” Tezuka examined the earliest days of human habitation on the Japanese islands, and the wars of conquest waged between different tribes, just as they had been between humans, Fumoon, robots and other races in his science-fiction work. He also introduced the bird of fire, the Phoenix, the embodiment of the cycle of life and death of the universe and the force which effectively governs karma and reincarnation, and whose blood is capable of bestowing immortality and thus giving unique exemption from the universal law of death.

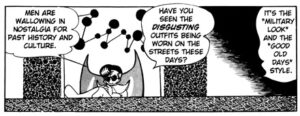

In the second chapter, “Future” written from 1967 to 1968 while Vampires was on a two year hiatus, Rock had a chance to encounter the creature which governs his many doomed reincarnations. This chapter takes place in the far distant future, and Rock plays the part of the well-disciplined soldier, gun always in his hand, closely resembling his role in the Metropolis movie. He serves as the chief of police for the computer Hallelujah, which runs an underground city, one of the five last fortresses where mankind still lives, hiding from the dead and polluted surface of an earth long-since destroyed and abandoned. This is the extreme temporal limit of the Tezuka universe, the farthest point when the frontier of space has been so thoroughly explored that all that remains is a backward-looking civilization lost in its own nostalgia, without progress or ambition.

Rock Following Orders

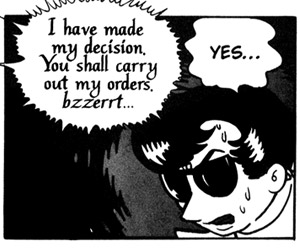

The computer Hallelujah is Rock’s mother, commander and creator, having literally chosen the gametes which were artificially combined to create him, thus intentionally choosing Rock as her champion, from among all the recurring characters she could have picked. Hallelujah’s command for her champion: exterminate the moopies, a race of sentient transforming creatures which live with humans as pets and companions, capable of transforming into any form their masters wish, and even of transporting their masters’ minds into dreamscapes of their choosing. The last moopie in existence lives with one of Rock’s subordinates, Yamanobe, a romantic dreamer who does not have the courage or curiosity of Tezuka’s boy detective heroes, but is content to live in fantasy.

Hallelujah’s order to exterminate the moopies seems strange on its own, particularly as she insists that the moopies will result in the destruction of humanity if they are allowed to live. But in every one of Tezuka’s earlier first encounter stories contact between humans and aliens has always degenerated into war, so the computer’s prediction that this other race living among humans will cause destruction is entirely justified. Rock is the perfect champion to fight the moopies, since he is the Transforming One, the king of vampires, master of disguise, the character who knows best what a transforming creature is. Rock is also the first Tezuka hero to have accepted the fact that evil means are sometimes best, and is thus willing to trust Hallelujah’s prediction and exterminate a seemingly benevolent race, as Kenichi, Astro and Yamanobe never could.

Rock behind the desk

As is typical of Phoenix, the true threat posed by the moopies will not be fully clear until the release of Phoenix: “Nostalgia” four years later, a chapter in which Rock does not appear himself. This chapter takes place several millennia before “Future,” and shows humanity at the stage when space colonization is common and contact with aliens frequent, but life on the frontier is still harsh and the necessities of survival in space are similar to the struggles of our most ancient ancestors in the early chapters of “Dawn” and “Yamato.” Now that humanity has multiplied and spread throughout the universe, the powerful force of nostalgia has set in, nostalgia for Earth, the home world many space-born colonists have never even seen. The formerly-constant drive to expand and explore is waning, as a desperate and self-destructive desire to return home, even if only to die there, is beginning to turn humanity into the hopeless, progress-less, backwards-looking society Hallelujah ruled in “Future.”

As for moopies in “Nostalgia,” they live on an isolated asteroid, trying to avoid contact with other races who would do anything to get their unique abilities to transform, adapt to any environment, and escape into a nostalgic dreamscape. Here the Phoenix herself recruits one moopie to aid a group of humans on the verge of extinction, since a single moopie’s ability to adapt and change lets her easily survive where humans have failed despite extreme struggle and suffering. Indeed, the moopie’s ability to adapt easily to any environment effectively mocks and undermines the nobility of the horrific struggles against extinction endured time and time again by humans and aliens alike in “Nostalgia,” and other chapters of Phoenix. How can the suffering of others remain meaningful while moopies can do the same effortlessly? And why would anyone struggle to progress and explore a harsh world and harsh universe when they can escape into Nostalgia in the imaginary idyllic Earth of a pet moopie’s dream world?

Rock Makube: Do or Die!

The moopies of “Nostalgia” agree that they must be kept apart from other races to keep both from degenerating. Hallelujah’s order to exterminate the moopies of “Future,” then, is a desperate attempt to wake humanity up from its nostalgic slumber and to jump-start struggle and progress once more. It is cruel, but necessary, and far less cruel than the solution the Phoenix will choose, jump-starting the struggle by exterminating all life on Earth and making us crawl up from the slime again. Rock, then, is the perfect avatar for Hallelujah’s final attempt to save mankind. After all, Rock has exploited the unfair advantage of transformation in many lifetimes, Rock struggles and suffers in this last life as much as in any life, and most important, Rock’s speech to Yamanobe about the degeneration of mankind and the danger of nostalgia demonstrates that he, perhaps unique among remaining humans, recognizes how far humanity has fallen. Note that Saruta, Ochanomizu, Astro and other champions of progress and exploration do not appear in this last, degenerate period of mankind.

Rock Makube: Samurai

In 1969, the year after the publication of Phoenix, “Future”, Tezuka made the connection between Rock and the moopies even stronger, by writing a the second section of Vampires. Here, for the first time, he presents multiple incarnations of Rock in the same story, briefly portraying several different previous incarnations of Makube Rokuro in the samurai period. Here he comes into conflict with the Ueko, a race of cat-like sentient creatures capable of transforming into human form, and imitating any human they see, just as moopies can. In his old incarnations Rock repeatedly wrongs and kills the Ueko and is in turn wronged and killed by them, effectively establishing a karmic conflict between him and these transforming creatures who destroy one another in life after life. After these flashbacks to previous lives, we return to our usual Makube Rokuro in the modern day, who, after his vampire army was thwarted, is invited to investigate the Ueko by a scientist who knows Rock has a special ability to command transforming creatures.

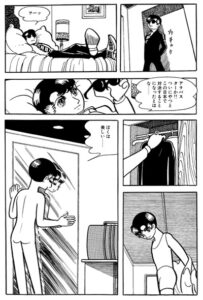

Rock finds an Ueko, which immediately transforms into his shape (just as the clay people did in Adventures of Rock). Here, instead of befriending the Ueko, Makube immediately enslaves it. As with the vampires before, he seems to have an unnatural ability to command the Ueko, exercising an almost-hypnotic control over it with his eyes. There follows a long and graphic sequence of Makube’s brutal training as he teaches the Ueko to act like a human, flogging, starving and torturing his own meek and peaceful likeness, insisting, “I will make a human out of you.”

Unfortunately, the Ueko section of Vampries was never finished, so we do not know how Makube’s plans to dominate the world using his personally-trained transforming slave would develop, but we can seek answers in other works, particularly the Phoenix volume of the year before.

Unfortunately, the Ueko section of Vampries was never finished, so we do not know how Makube’s plans to dominate the world using his personally-trained transforming slave would develop, but we can seek answers in other works, particularly the Phoenix volume of the year before.

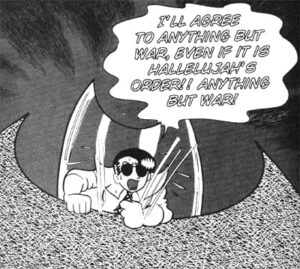

In “Future”, the Phoenix makes no attempt to hide or conceal itself behind superstition, but appears boldly in front of Rock and Yamanobe. It communicates to Yamanobe telepathically, declaring that it controls life and death, that it can grant immortality to whom it will, and that it has chosen to let humanity be destroyed and remade. It even grants him a vision of the entire macrocosm, and the system of reincarnation, almost identical to the vision received by Buddha in Tezuka’s biography begun four years later. Rock receives only a brief summary of the Phoenix’s words from Yamanobe, but it is enough to communicate the fact that the universe is governed by an inhuman creature which rules over death and immortality. More important, as the Phoenix grants Yamanobe immortality and abandons Rock, Rock sees himself actively rejected by the Phoenix, who Yamanobe the immortal instrument of Earth’s regeneration, and leaves Rock to perish with the old world as he watches Hallelujah and the other computers which control the remnants of mankind destroy one another in one last, inevitable war.

Rock: Phoenix (War)

Many readers are unsettled by the Phoenix’s choice, not only because of the simple injustice of choosing one over another, but because the fiercely-determined and passionate Rock is more appealing than the frail and nostalgic Yamanobe, who seems to personify the degenerate world of “Future” while Rock is closer to humanity’s grim but determined past. Viewed from the larger perspective of multiple incarnations, however, Rock’s place in the universe is not an instrument for the creation of life, nor as a hero who retains his love of life throughout trials, which is what the Phoenix needs to recreate life. Rock is the transforming one, one who embraces the evils learned over a short and dramatic lifetime and becomes corrupted through suffering. He cannot, as Yamanobe does, endure millenia of solitude, watching life crawl back from the slime again, and remain tender and kind as Yamanobe must. Rock also wishes to preserve himself and his own life more than others, and even abandons Hallelujah and his homeland to save himself when he sees no way to stop the war; Astro would have stayed and kept on fighting to the bitter end.

Meet the Phoenix

The Phoenix, then, has not rejected Rock in this moment or this one incarnation. Rather, Rock is locked into his recurring role in the reincarnation system – he is a transforming creature, not a creator of life. Yamanobe, on the other hand, loves life, and does fight to cultivate it, not here in his nostalgic form, but in another incarnation in Black Jack #127, “Devotion to Medicine.” Here the dying young doctor Yamanobe struggles desperately for a chance to save at least one human life before he dies, because he insists there is no afterlife, no second chance, and the most important thing is to fight against death and create what little life we can. The Yamanobe in Phoenix may not understand why he gets to be the new creator, but it is the answer to a different Yamanobe’s prayer, a Yamanobe who, living before the onset of nostalgia, represented humanity’s eternal struggle to preserve life far better than Rock ever could.

Immortal Rock

We are left to wonder, then, why the Phoenix chooses to show itself to Rock at all, let him become aware that it has refused him immortality and doomed him to fight his battles over infinite incarnations. It could be assumed that Phoenix manifests at least once to any given soul once to explain its role, as she does for many over the course of Phoenix. At the same time, it is hard not to see some relationship between Rock in Phoenix receiving proof of the existence of reincarnation, and Makube in Vampires, in the same year, facing his death with the calm certainty that he will return to fight the same battles again.

As Rock’s part in Phoenix “Future” closes, we see him dying of radiation sickness, sitting above the liquid lava crater which was once his home. He is the last surviving human now that Yamanobe has become something else, and as he dies he does not cry, or pray, or protest his fate, even though he knows, at last, that there is a Phoenix out there listening. Instead he sits back to enjoy the beauty of the view and laughs. As in Vampires, Rock faces death with a calm confidence which lets him mock the absurdity of his own position in the universe. And it is only proper that a character who is aware of the fact of his own reincarnation and constant struggle be the one chosen by Hallelujah to make one last, doomed effort to exterminate the moopies and to get a nostalgic, lazy humanity to struggle once more.

Another Death of Rock

Makube

It was prophesied in Vampires that Makube would become king. Now that we are reading his many incarnations together, this does not necessarily refer only to Vampires. Perhaps Makube’s dominion over the transforming creatures means that he would be, or in some sense already always was, the king of transforming creatures. Perhaps, ironically, he became king in Phoenix when all other humans in the world were dead. Perhaps it is a retroactive prophecy, referring to Rock’s status as the effective king of the planet in in Adventures of Rock of which he was the owner and first colonist fourteen years earlier, or perhaps it looks forward to other royal incarnations he would have in other works in the following decades.

Live Action Rock

Rock, or rather Makube, also appeared in the unfinished 1969 live-action TV series of Vampires. This innovative series spliced animated werewolves and other animals into live-action footage to create one of the first animated/live-action hybrids. The series was left unfinished and Tezuka himself said he was very dissatisfied with it, though it is still interesting to see, particularly since Tezuka played himself in the live action adaptation.

TANGENT: 1968 – PRINCE NORMAN and PRINCESS KNIGHT TV

In 1968, Tezuka wrote a short, well-polished science-fiction adventure series called Prince Norman which followed a set of humans with supernatural powers who are taken back in time 500 million years to fight to defend an interstellar empire which then flourished on the moon, long before the development of Earth civilization. For those familiar with Tezuka’s star system, the most striking character in the manga is the young English assassin David Flight, who can only be described as “not Rock.” David and Rock have the same body type, proportions, posture, speech patterns and similar hairstyles. Like Rock, David has characteristic sunglasses, though David’s are light while Rock’s are black, and David’s special ability, in the capacity to see through walls, brings attention to his eyes just as it was brought by Makube’s hypnotic abilities in Vampires. Yet, when David finally takes the sunglasses off, his face is very distinctly not Rock’s.

To make the comparison even more striking, David’s personality and background contain characteristic elements which appear repeatedly in Rock’s many incarnations. David is a professional criminal, a skilled assassin and unhesitating killer, young and precocious, with a criminal confidence similar to that of Makube Rokuro. His sufferings as he is forced into military service, and beyond that forced into darker activities, are strikingly similar to those Rock was forced into in Nextworld, as is his fierce and futile rebelliousness. Indeed, the more one reads, the more his reactions in all situations are precisely what one would expect from Rock, and one is led inevitably to the question: Why didn’t Tezuka just draw Rock in this role?

The answer lies partly in the timing. Tezuka began writing Prince Norman during the hiatus between Vampires I and II, and mid-way through the serialization of Phoenix “Future”, and finished it a few months before the publication of the second part of Vampires. This places Prince Norman in the middle of the most critical period of Rock’s development, so it is understandable that Tezuka was not prepared for Rock to appear in another series while he was in the middle of this fundamental change. To borrow the terms of the Star System, Rock was busy elsewhere, and David was the understudy.

But there are other, deeper reasons why Rock could not fill the role of David Flight in Prince Norman, reasons which further highlight the few characteristics of Rock which never change, even in the most unusual roles. David’s part cannot be played by the Transforming One. David is an Earthman among aliens, an Englishman among foreigners, and a civilian assassin forced to play the role of soldier. He does not fit, and does not want to fit, into this new role; he does not change. Rather David suffers because of his unwillingness to adapt to military life, or to accept the ideals of Prince Norman and his people.

More specifically, if Rock is the King of the Transforming Creatures, he would have a very different position from David in a series in which the enemy are aliens whose most dangerous power is transforming into the forms of others; even if Rock could not command them, it would be implausible to think he would not be able to see through them. In addition, David’s goal in the series is to return to his home, nothing more, nothing less. He is neither ambitious nor forward-thinking, but effectively crippled by nostalgia for a homeland which he knows does not even quite exist. The backwards-looking, nostalgia-infested world of Phoenix “Future” offered us (and Rock) a glimpse of dangers of this kind, fully explored in the “Nostalgia” chapter in 1971. But by then Rock had undergone yet another transformation.

David Flight did not go on to have a role as a recurring character in Tezuka’s universe but remained a one-time figure, a substitute Tezuka would never need again. Rock, meanwhile, still had more than twenty lives to go.

From 1967-1968, Rock also featured in the Princess Knight TV series in the very light role of Sapphire’s true love, a part he would play again in Marine Express and other lighter animated works. This is a striking example of a light Rock appearing in contrast with his newfound darker aspect. Partly his appearance is symptomatic of the fact that Tezuka was somewhat dissatisfied with the original Princess Knight manga, and of the fact that he was always pressured to make animated adaptations of his works lighter than the originals. Still, it stands as a testament to his continuing intention to preserve Rock as a hero as well as a villain, since he is cast here as the romantic lead in a Disney-style fairytale, and it also stands as evidence of his producers’ confidence in hero Rock’s continued popularity, since they could easily have vetoed the change if they had thought Rock had become too dark for viewers to accept him as a handsome prince. The Transforming One is an appropriate selection as a romantic partner for Sapphire, who changes from male to female, and it is interesting to note that he was not inserted into this part in Princess Knight until 1967, when Vampires and Phoenix were establishing his transforming nature more firmly, and when he had, for the first time, begun to be drawn as effeminate and to appear in drag. Rock is not feminized in Princess Knight TV, but his marriage to the man-woman Sapphire would come only a year before his first fully feminized and actively homosexual role.

Section 4: UNFORGIVABLE

Rock Makube: FBI

By 1969, Rock had committed parricide, arranged assassinations, practiced slavery, inflicted torture, betrayed family, backstabbed friends, abandoned lovers, attempted rape and kidnapping, attempted to kill his own author and had been personally responsible for the deaths of thousands. Nevertheless, Rock’s appearance as an FBI agent in the series Alabaster, published from 1970 to 1971, stirred a wave of outrage among Tezuka’s readers, resulting in a deluge of letters expressing shock and anger at Tezuka for making Rock’s new incarnation so evil. What made this version of Rock, known simply as “FBI,” so much worse than Makube?

Rock makes a call

Alabaster is a treatment of the desire within ugly creatures to destroy the beautiful, and the inverse tendency of the beautiful to oppress the ugly. The central character James Block was once handsome but hideously transformed by a malfunctioning invisibility ray, and he spends the series maiming and murdering as he attempts to transform the world in his own image. Rock is the FBI agent assigned to track and capture Alabaster and his band, taking the role which used to be reserved for a boy detective, or for the charming old man Shunsaku Ban, but here the detective may be worse than the criminal.

Rock in drag

The attacks of conscience and humanity Makube experienced in Vampires, mirrored in moments of hesitation in Phoenix, are completely gone in Alabaster. We are left with a villain who never hesitates. Sadism has entered Rock’s repertoire for the first time as well. While Makube had no qualms about torturing innocents to achieve his ends, and certainly took pleasure in his success, he never actively sought to cause pain to others exclusively for the sake of watching his victims suffer. And Rock’s selfishness, a tendency he had from the very first, has here advanced beyond mere ambition to a very unsettling Narcissism, personified by what has become Alabaster‘s signature image, that of Rock admiring and caressing his nude body in the mirror.

Here Rock’s effeminacy has advanced beyond Makube’s simply donning female disguises, to an actively feminine face and body-language which are revealed only when he removes the sunglasses. This sensuality pervades the narrative of Alabaster, Rock’s villainy is, for the first time, sexual. While Rock had engaged in some tragic romances in earlier series, here he is a seducer and a rapist. Rock gained his position in the FBI by sleeping his way to the top. FBI has seduced both men and women, often adopts female guise, and commits rape for the sheer pleasure of domination. Indeed, the visually stunning sequence of FBI, while in female clothes, raping an invisible woman is such an unsettling blend of cruelty, narcissism and gender ambiguity that it serves as a portrait of how the beautiful can be vile at the same time, personifying the beautiful but tainted world which Alabaster seeks to destroy.

Rock the rapist

The closest Rock had come to rape before this was in Phoenix “Future,” where he attempted to carry off and rape the female Moopie in order to repopulate the all-but-extinct human race, but this was an expression of an animal instinct necessary in these extreme conditions, and experienced by many characters elsewhere in Phoenix as Tezuka teaches time and time again the lesson that, in a survival situation, life must go on whatever the cost. In Alabaster the rape is committed for pleasure and for power.

The Face of Evil

The highly-sexual Rock marks not only a new stage in Rock’s development, but a new stage in Tezuka’s treatments of evil, developing toward the complicated homosexual power of Yuki in the extremely grim MW (1976-78). Yuki is the most horrible, sadistic, sexual and charismatic villain Tezuka ever wrote, and also effeminate, also a master of disguise, and undeniably an extension of Rock’s villainous development. Yuki is not Rock, critical differences in their faces and body structure make that clear.

Yuki is also not another understudy like David Flight in Prince Norman. Instead, Yuki is a monster, step beyond Rock, bent not on ambition but destruction. Yuki is not the result of an ordinary human embracing the utility of evil, not the result of choice, but an unnatural creation generated by a small child being exposed to a hideous poison, and to the equally poisonous experience of walking through the aftermath after a genocide. But Yuki is very clearly an extension of Rock’s development, using many of FBI’s techniques, donning disguises, almost always involving Rock’s characteristic sunglasses, and even admiring himself in the nude in panels which are a clear parallel of Alabaster.

Yuki getting ready

If Rock’s fans, reading Alabaster, complained to Tezuka that FBI was not Rock and that he was committing sins Rock never would, then Tezuka has responded to them in MW by showing them a real monster, someone who really is worse than Rock could be. FBI is still ambitious, still human, still a boy who recognizes the utility of evil and uses rape and seduction to achieve power. FBI is still the transforming one, partly a civilized and partly wild, while Yuki is pure monster.

In an almost reversed striking contrast, Yuki is also not Rock because he retains love, in his case a sick and cruel love for the priest Gurai who is unable to resist his seductive power. Rock, whom we have seen easily turn his back on love in Nextworld, Phoenix and elsewhere would never maintain a relationship with a lover whom he knew was a danger to him and his plans. Rock learned early that friendship and love are not useful in the struggle for power, or for survival, a knowledge shared by the other vampires who retain the beast-like power to pray freely on members of their own race. Yuki lacks this; he is not an animal but a human monster, created by war and the other sins of civilization, and he maintains a civilized love, even if one twisted. He is a step away from Rock and toward the new theme of twisted victims of war which Tezuka will explore in his treatments of the second world war, Adolf and Ayako. Rock, meanwhile, has reached the limit of his degeneration.

Leave a Reply