Tezuka’s Life (1928-57)

Osamu Tezuka (手塚 治虫) was born on November 3, 1928 to Yutaka (father) and Fumiko (mother) Tezuka. Although he was born in Toyonaka, a city near Osaka, the family soon moved to Takarazuka City, Hyogo – the home of the famous Takarazuka Revue. This theatre, known for its romantic musical works performed by an all-female cast, had a tremendous impact on the young Tezuka. Even before he was old enough to go to school, his mother would often take him to go see the latest Takarazuka Revue productions. Their often flamboyant costuming and set-design had a lasting and significant influence on Tezuka’s later works – especially those aimed at young girls. The eldest of three children, Tezuka took to drawing early on, and he was so prolific that his mother was often forced to erase and re-use many of his notebooks just to keep up with the demand. As he entered elementary school, all that drawing practice came in quite handy. Not naturally athletic, at first young Osamu was teased by his classmates. However his natural story-telling ability quickly manifested itself and Tezuka soon became quite popular for his amateur manga, often taking requests from his fellow students. Fortunately, these talents were nurtured and even encouraged by both his liberal-minded parents as well as a few sympathetic teachers at a time when drawing manga was seen by many as a frivolous waste of time.

A naturally curious boy, with an insatiable appetite for knowledge, young Osamu was interested in everything from class theatrical plays, to astronomy, to searching for insects in the woods near the school.”

A naturally curious boy, with an insatiable appetite for knowledge, young Osamu was interested in everything from class theatrical plays, to astronomy, to searching for insects in the woods near the school. Insects held a particular fascination for Tezuka, and he began not only hunting them, but also creating detailed drawings of their appearance and cataloging his finds. It was this love of insects that led to him append the Japanese character for insect, “虫” (mushi) to his name – thus creating his pen name “Osamushi Tezuka”.

In 1944, as the war effort in Japan became ever more desperate, the sixteen-year-old Tezuka, despite being still in high school, was drafted into full-time service at a military factory. While working there, he used every possible spare moment to draw – something that often drew the ire of his supervisors. His fellow workers, however, appreciated his efforts; one of his favorite places to hide and draw was the washroom, where his manga, drawn on the toilet paper, could be enjoyed in private. In truth, the war years had a profound effect on Osamu Tezuka. Having witnessed first-hand the horrors of the firebombing of Osaka, he never forgot mankind’s capacity for destruction and violence, nor the toll of human suffering it demands.

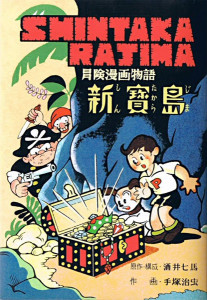

Yet, despite the war, Osamu Tezuka graduated High School in March 1945 and was accepted into the Faculty of Medicine at Osaka University in July 1945. This did not mean Tezuka had abandoned his pursuit of manga though, in fact far from it. Shortly after beginning his studies, a neighbor who was working at the local Osaka-based newspaper introduced Tezuka to an editor of the Manichi Shinbun. Impressed, he encouraged Tezuka to try his hand at 4-panel gag manga, and The Diary of Ma-chan (1946), his first professionally published work, debuted in January 1946. It was an instant success, and opened the door for Tezuka as a professional manga artist. However, a much bigger break was just around the corner. Later that same year, he received an offer to work on a story concept developed by another local (and more established) manga artist in Osaka, named Shichima Sakai, and he leapt at the chance to try his hand at long-form story manga. In fact, Tezuka was so enthusiastic his original draft was 250 pages long. However, Sakai had promised the publishing company Ikueisha a book of 190 pages, so he cut 60 pages from Tezuka’s manuscript. In the process, he changed much of the script and even retouched much of the artwork along the way. Although done primarily because of the way the pages needed to be laid out for publication, the rearranged story was weakened, with some plot elements shifted around or removed entirely. Furthermore, much of the new connecting dialogue was simplified because Sakai felt some sequences would be too complicated to understand for the young readers.

However, even with these drastic changes to Tezuka’s original vision, when New Treasure Island (1947) hit the stands in April 1947, it was an almost overnight sensation and quickly sold over 400,000 copies (a significant feat in a Japan still recovering from the ravages of the Second World War). It also introduced Tezuka’s cinematic storytelling techniques to the manga-buying public, cemented Tezuka’s status as a manga star, and arguably started the entire story manga genre in Japan. Flush with his early success, in the summer of 1947 Tezuka set off for Tokyo to try his luck with the major manga publishers. Given the general uncertainty in the years immediately following the war, his visit to Kodansha was unsuccessful. However, the trip did pay off as publisher Shinseikaku did decide to take a chance on The Strange Voyage of Dr. Tiger (1947), and the small publishing house Domei Shuppansha bought The Mysterious Dr. Koronko (1947).

Yet, despite the allure of Tokyo, Tezuka still had medical school waiting for him back in Osaka. At this point in his career, Tezuka was still juggling his priorities – not willing to give up on a well-respected career in medicine, but unable to deny his passion for manga. Although he continued on as usual, often drawing pages of manga during his medical classes, he did receive an important piece of advice from his mother. When Tezuka admitted to her that he preferred manga to medicine, his mother told him to do what made him happy. It was during this period that he was able to publish his great early “science-fiction trilogy” adventures Lost World (1948), Metropolis (1949), and Next World (1951).

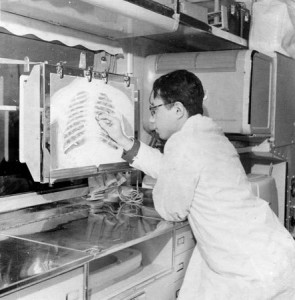

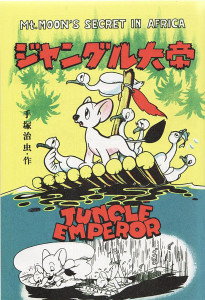

Of course, based largely on the success of his first serialized adventure manga, Jungle Emperor (1950-54), published in Manga Shōnen, eventually Tokyo came calling on Tezuka. Looking for new talent, Shōnen sent a staffer all the way to Osaka in an attempt to get Tezuka working for them. And so, in April 1951, one month after graduating from medical school (although with still one more year as an intern to go), Shōnen started the serialization of Ambassador Atom (1951-52). Despite having completed medical school, and becoming a licensed physician, Tezuka had made up his mind to pursue a career in manga. Although he never practiced, his medical knowledge would later serve him well as he worked on his three great medical dramas, Ode to Kirihito (1970-71), A Tree in the Sun (1981-86) and, of course, Black Jack (1973-83) – one of his masterpieces.

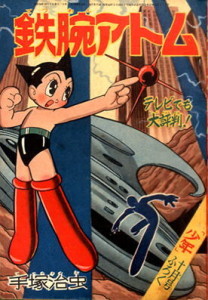

Although Ambassador Atom (1951-52) had been considered a moderate success, it did not do as well as Tezuka had expected. However, the young fans had been particularly taken with a relatively minor character in the series – Astro Boy. As such, the editor of Shōnen suggested that Tezuka make the little robot the main character of the follow-up serial, but to make him warmer and more human-like. And so, Astro Boy (1952-68), one of Tezuka’s longest serials, featuring one of his most well-known and well-loved creations, began publication in April 1952.

The late 1940’s/early 1950’s were a “Golden Age of Manga” in Japan, and Tezuka quickly found himself the object of a large and very creative fandom. A number of his fans began to bombard him with letters, often enclosing their own manga work in search of advice or critiques. On occasion, a few of them would even turn up on his doorstep, samples in hand. Despite his busy schedule, Tezuka would take the time to engage them, often with discussions lasting until late at night.

In the spring of 1952, Tezuka finally moved full-time to Tokyo after spending most of the year commuting back and forth from Osaka, and by the summer of 1953 he had moved into an apartment building known as Tokiwa-so. Although the building would later become a haven for aspiring manga artists, only one other manga artist lived there at the same time Tezuka did. Even though he only lived at Tokiwa-so for a year and a half, he created many of his famous early works there, including: Princess Knight [Shojo Club] (1953-56), an adventure story aimed at young girls, the roots of which can be traced directly back to his days at the Takarazuka Revue; Crime and Punishment (1953), another experiment to transform a literary classic into manga; and Phoenix [Manga Shonen] (1954-55), the very first incarnation of what would come to be known as his life’s work. His time at Tokiwa-so also marked the beginning of one of Tezuka’s favourite pastimes, and one that would follow him throughout his career – playing “hide and seek” with his editors.

Although he spent almost every waking hour drawing manga, Tezuka often over-extended himself professionally. As a consequence, editors from the various publications serializing his manga would track him down and wait by his side as he finished page after page of artwork. It was such a common occurrence that his editors resorted to playing games of “rock, paper, scissors” to decide who’s pages he would work on first. This, in turn, led to Tezuka finding multiple hidden “safe houses”, often out-of-way local hotels, where he could work on his manga in peace.

At times, the workload became so overwhelming Tezuka would call upon other local manga artists to help him. This would usually mean a few manic days of work, with Tezuka providing the overall direction as well as the finishing details, and the junior manga artists drawing the basic character poses and backgrounds. Although the other artists learned a lot from working with Tezuka, it was not a sustainable situation. As such, in 1957 he rented a house and converted it to a proper studio. He also formally hired art assistants and an agent to act as his go-between with his many editors.

As he worked regularly with assistants, Tezuka developed a type of graphic short hand that let him communicate his wishes to them more easily. By simply annotating his pages with a type of code, he could let his assistants know which background fill (i.e. dot patterns or cross-hatching) and/or colour to use. The system was so efficient, it even allowed him, often working from memory alone, to send instructions to his assistants over the phone.

A huge fan of the cinema, Tezuka also approached his movie going with the same level of efficiency. Despite his inhuman schedule, he was an avid reader of film industry magazines. Using the articles and reviews, he’d separate the movies he wanted to see for the story, from those he was interested in only for the cinematography. He’d then calculate the run times and plot a schedule that would allow him to move from theater to theater to see only those scenes that interested him. Using this system, he was able to see upwards of 350 films per year.