Tezuka’s Life (1965-72)

By 1965, Astro Boy (1963-66) was already entering it’s third year in production, Mushi Productions had started work on a new animated television series known as Wonder 3 (1965-66), and was gearing up for it’s latest ground-breaking series – the first full-colour animated television program in Japan, Jungle Emperor (1965-66). Looking to follow up on the success of Astro Boy (1963-66), NBC approached Tezuka with a request for a new program. Although they were happy with Tezuka’s pitch for Jungle Emperor (1965-66), they were adamant the series had to be produced in colour. Since Mushi Productions did not yet have the capability of colour production, NBC agreed to help finance the necessary upgrades.

While NBC’s interest in Astro Boy (1963-66) had been a pleasant and unexpected surprise, however, because Jungle Emperor (1965-66) was produced for both domestic (Japanese) and overseas (USA) markets at the same time, several major accommodations were made. The first of these was an almost complete ban on violence, especially bloody violence and death. Also, the very idea that the series star (i.e. Leo/Kimba) would die in the final episode was a concept completely foreign to American audiences at the time. Given these constraints, NBC felt it was much better to concentrate simply on Leo‘s adventures as a young cub. In this way the young audience would identify better with the main character, while at the same time it would also make it easier for local television stations (the lifeblood of network television) to air the episodes out of sequence. Although this significantly changed Tezuka’s original premise, he agreed based on a promise from NBC to continue the series Tezuka’s way should the first series turn out to be a success.

And it was a success. Jungle Emperor (1965-66) debuted on Fuji TV on October 6, 1965 and completed a very successful run of all 52 episodes on September 28, 1966. However, given the tight production-to-broadcast schedule (roughly a week after completion), the decision was made to wait until they were all completed before they were sent to NBC for re-dubbing and editing. And so, the newly re-titled Kimba the White Lion premiered on American television in late 1966/early 1967 – the beginning of a long and successful run on NBC and in syndication. Meanwhile, since it was such a hit in Japan, Osamu Tezuka felt emboldened enough to charge ahead and invest his profits back into the sequel. Premiering on October 5, 1966 (the very next week after the end of the first season), Jungle Emperor: Onward, Leo! (1966-67) began a second season 26-episode run that ended on March 29, 1967. Relying on NBC’s promise to continue the series as Tezuka wanted, Jungle Emperor: Onward, Leo! (1966-67) was set roughly five years after the events in the original series – with Leo and Lyre were now adults, married with children.

However, Tezuka’s ambitious plan backfired on him – by not consulting NBC (so as to avoid further tampering), Tezuka was able to steer the series back towards its initial intent. However, this drastic change of course created a general disconnect between the two series – one that left audiences cold. So while Jungle Emperor: Onward, Leo! (1966-67) was well-received, it was not as popular as the original. More seriously, NBC had not even known that Tezuka was working on the sequel until he presented it to them as a complete package. Unsurprisingly, the new series contained too many changes for NBC’s tastes – many of which they had specifically told Tezuka only a year or so earlier they did not want – and they declined to purchase the series.

In NBC’s opinion, the new series was not a continuation of the original series but rather his rejected original Jungle Emperor proposal, however in Tezuka’s eyes this was a betrayal and soured his working relationship with NBC.

Throughout this period, Tezuka was also working on experimental animation film projects. Usually non-commercial, these short films were intended to be works of art to be shown at animation festivals – many award-winning. His first project, Tales of a Street Corner was released in 1962, and was soon followed by Male (1962), Memory (1964), Mermaid (1964), The Drop (1965), Pictures at an Exhibition (1966), and The Genesis (1968).

In 1966, Mushi Productions moved its corporate office to the Ikebukuro area of Tokyo, and, inspired by alternative and avant-garde manga being published in Garo, decided to begin publishing cutting edge manga in a magazine named COM – featuring a new series by Tezuka known as Phoenix (1967-88). In December that same year, Astro Boy (1963-66) came to an end after 193 episodes, with Astro tragically flying into the sun and sacrificing himself to save the Earth. Mushi Productions followed up Astro Boy (1963-66) with The Adventures of Goku (1967) an adventure/gag series loosely based on Son-Goku the Monkey (1952-59), before deciding on Princess Knight (1967-68) as the next Tezuka work to be animated.

Although Tezuka had hoped Princess Knight (1967-68) would be of interest to NBC, given its European-style fairytale setting, NBC felt differently. According to Fred Ladd, in his book, Astro Boy and Anime Come to the Americas, NBC declined to purchase Princess Knight (1967-68) primarily because of the girl-dressed-as-a-boy gender bending aspects of the series. NBC was concerned that “station buyers who would either buy, or reject, this series would reject it, on their perception that this series was all about “sex switch” (2009, p. 68). Despite this setback, Mushi Productions went ahead with the production and the Princess Knight (1967-68) animated television series debuted on Fuji TV on April 2, 1967. One of the fist animated television programs aimed at a young female audience Princess Knight (1967-68) was a hit and completed its 52-episode run on April 7, 1968.

1968 was a year of big changes in the manga industry. With the growing geikga movement pushing for a more realistic approach, manga aimed specifically at young boys began to lose momentum. One example of this was Shonen, the home of Tezuka’s long-running series Astro Boy (1952-68) ceased publication after 23 years. Although Astro Boy (1952-68) began a serialization in the Sankei Newspaper, seinen manga titles such as Manga Action, Young Comic, Play Comic and Big Comic, with stories geared more for an audience of young men, began appearing. Intrigued by this shift, Tezuka began serializing his first manga stories aimed at an older audience, with Swallowing the Earth (1968-69) in Big Comic and Under the Air (1968-70) appearing in Play Comic. Also, partly in response to these changes, Tezuka decided he needed a separate company to handle his manga projects and so Tezuka Productions was born.

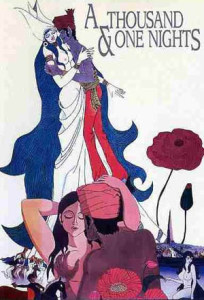

This shift in the late 1960’s also had an impact on Mushi Productions’ animation projects. By early 1969, work was progressing at a feverish pace on A Thousand and One Nights (1969), Tezuka’s first animated big screen film aimed at an adult audience. Envisioned by Tezuka as an “animerama” (an abreviation of “animated drama”), which explored the possibilities of animation technology and cinematography, this massive undertaking required the help of every artist working at both Mushi Productions and Tezuka Productions to complete. With Tezuka himself only sleeping about two hours a night, A Thousand and One Nights made it to the theaters in June 1969 – premiering on the same day Tezuka’s second daughter, Chiiko, was born.

Always concerned with his audience, Tezuka went to the theater every week to gauge public reaction for himself. Despite some mixed reviews, the film was considered a hit as it more than covered its production cost of ¥130 million by bringing in a reported ¥320 million in revenue for a total profit of ¥90 million.

The moderate success of A Thousand and One Nights (1969) led Mushi Productions to work on another even more sexually charged adult film and Cleopatra was released in September 1970. However, without the novelty factor inherent in A Thousand and One Nights (1969), Cleopatra (1970) was largely given a pass by audiences of the time.

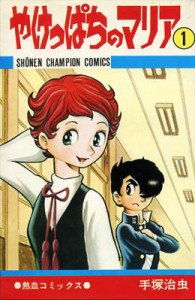

By 1970, in an attempt to try and recover ground lost by the introduction of seinen manga a few years earlier, as the shōnen manga aimed at young boys began to introduce more and more erotic elements into their stories. This, in turn, began to skew the audience for shōnen manga to an older demographic. For many, this conflict with the somewhat traditionally repressive elements of Japanese society sparked a national debate on the sexual education of youth. Never one to shy away from a controversial topic, Tezuka dived right in with Apollo’s Song (1970), a relatively dark story based on the cycle of procreation and the role of love, and Yakeppachi’s Maria (1970), a more upbeat tale of an ectoplasmic doll brought to life by a young man’s sex drive.

Tezuka also tackled the question of children’s sex-education with Marvelous Melmo (1970-72), the story of young girl with a jar of magic pills that let her instantly adjust her physical (but not mental) age. By transforming physically into a mature woman lets Melmo have adventures that explore various elements of adult life, including different careers, romance and sexuality, through the eyes of a child.

Tezuka felt betrayed by the company he had thought of as his own child…”

By 1971, Mushi Productions had already drifted away from simply being an outlet for animating Tezuka’s works, and in June 1971, Osamu Tezuka stepped down as its CEO. Years of producing animated television programs with the thinnest of financial margins, expensive big-screen film explorations, and non-commercial experimental works had taken a toll on the company. As such, there was a growing push from within to stop following Tezuka’s every artistic whim and focus on more commercially viable projects. Tezuka felt betrayed by the company he had thought of as his own child, but, by this point, it was already a very different place than he’d originally envisioned. As a result of leaving Mushi Productions, Tezuka also lost clear legal control over the animated versions of his own works – including Astro Boy (1963-66)!

Yet, though he had left Mushi Productions, he had not given up on animation. Starting with a staff of just four animators that had followed him from Mushi, the newly created animation department of Tezuka Productions began working on a new animated television series. Remarkably, by October 1971 the animated version of Marvelous Melmo (1971-72) began a somewhat infamous 26-episode run. Broadcast in full-colour on the Asahi Broadcasting Network (TBS), from October 1971 to March 1972, Marvelous Melmo (1971-72) was a hit with children, but many parents hated the show since it raised so many questions they were uncomfortable with answering.

With only one animated series to occupy him, Tezuka also turned much of his attention on his manga work, and Lion Books (1971-73) was reborn. Originally published in Omoshiro Book by Shueisha, Lion Books (1956-57) had been a series of short sci-fi stories – many of which can be considered ahead of their time. Returning to this concept over ten years later, Tezuka surpassed his earlier efforts with another series of independent short stories published in Shonen Jump (shōnen jampu).

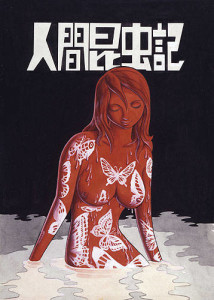

However, by the early 1970s, Tezuka’s major manga works became increasingly dark – brought on, in part, by his own personal setbacks, such as the loss of Mushi Productions, and in part by the general turmoil of Japanese society at the time. Tezuka’s “dark period” was quite different from his earlier attempts at presenting adult themes in manga, such as Swallowing the Earth (1968-69) and Under the Air (1968-70). Although those works had a much more serious tone than his earlier “boy adventure” stories, they were still approached in a somewhat light-hearted way. However, works such as The Book of Human Insects (1970-71), with it’s soul-stealing female protagonist who will stop at nothing to become rich and powerful, Alabaster (1970-71) with bleak and hopeless story of a heartless killer, and Ayako (1972-73), the story of a young girl imprisoned and abused by her own family after the Second World War, present a very different approach to serious story-telling.

While somewhat controversial, and not universally liked, they reflect and important stage in Tezuka’s work and life, however, there is one possible exception. After Tezuka Productions’ magazine COM folded in 1972, Tezuka’s series Phoenix (1967-88) was left homeless. Soon afterwards, he received an offer from the publisher, Ushio Shuppan, with a suggestion that Phoenix (1967-88) be continued in Hope’s Friend. While Tezuka thought the magazine’s audience was a bit young for Phoenix (1967-88), he suggested a biographical series on the historical figure of Siddhartha. And so, Tezuka’s semi-fictionalized biography of the Buddha (1972-83) began in the spring of 1972 and ran for 11 years, until 1983.