Tezuka’s Life (1958-64)

In 1958 Tezuka had two meetings that would shape his life. The first was a visit by staff from Toei Animation who were interested in developing Tezuka’s manga series, Son-Goku the Monkey (1952-59) as an animated feature film. Known as Saiyuki, the film was released in August 1960 and although he was only a consultant on the project, it was the first of Tezuka’s works to be animated. More importantly, though, his involvement gave him behind-the-scenes access to the inner workings of an animation studio – something that would pay off later in his career.

The second was an arranged meeting with Etsuko Okada, a young woman from Tezuka’s hometown of Takarazuka. The two soon began dating and a little over a year later, they were married in a ceremony held in October 1959 at the Takarazuka Hotel. True to form, Tezuka arrived late to his own wedding dinner because he had to finish up a few urgent pages of artwork for a waiting editor. Besides being a homemaker, Etsuko was also an invaluable sounding board for Tezuka professionally. Since he was otherwise surrounded either by assistants worried about their work going to waste or editors worried about missing a deadline if something had to be re-drawn, Tezuka was able to rely on Etsuko’s opinion if he felt unsure about the quality of his work.

Feeling that both his home and work life were now stable, Tezuka began to turn his attention to his dream of opening an animation studio. The first step, in August 1960, was to the construction of a combination home/studio in Fujimidai, on the outskirts of Tokyo. On the one hand, this allowed Tezuka’s aging father and mother to leave Takarazuka and move in with the young couple. On the other, it established a more permanent base of operations for his work – something he would need in order to establish an animation studio.

However, before he could fully devote himself to his goal, there was one more thing he needed to take care of.

Although Tezuka had chosen a career in manga, he never lost his love of medicine and science. And so, in January 1961, after years of intermittent lab work done during short breaks in his manga work, Tezuka completed his theses – Electron Microscope Study on Membrane Structure of Atypical Spermatids. In February he received his PhD from Nara Medical University.

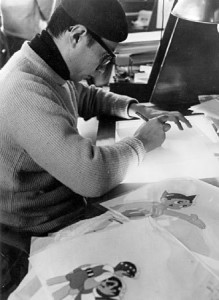

With that out of the way, Tezuka could now focus on animation. Although not yet operating as an actual studio, Tezuka began gathering young artists interested in animation. Working out of the cramped quarters of his manga assistants’ workspace, the first production they began working was Tales of a Street Corner (1962), with Tezuka paying for all the equipment and salaries out of his own pocket. In effect, his manga work was financing his foray into the world of animation, or, as Tezuka was fond of saying, that if manga was his wife, then anime was his mistress.

By August 1961 Etsuko had given birth to their first son, Makoto Tezuka (to be followed by his daughters Rumiko in 1964, and Chiiko in 1969), and by September, Tezuka started construction on a proper animation studio next door to his home/manga studio, and Mushi Productions was born.

Although the close-knit staff was interested in animation as an art form, it soon became obvious that Mushi Productions would not be sustainable without a marketable product. On the one hand, as a small, independent studio, Mushi Productions would not be able to produce animated features of the same quality of Walt Disney or Toei Animation. On the other, simply producing animation for television commercials would be an unsatisfying and most likely frustrating experience. As such, Tezuka decided to attempt something that, to that point, had never been tried in Japan – a weekly, television anime series.

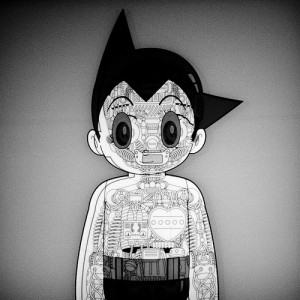

With that, the original Black & White Astro Boy (1963-66) animated television series was born. Tezuka immediately split his animation studio team in two – with half continuing to work on experimental films like Tales of a Street Corner (1962) and the other half working on Astro Boy (1963-66).

Interestingly, Tezuka decided to produce Astro Boy (1963-66) as a loss-leader on a shoestring budget instead of trying to negotiate a more lucrative deal with a potential sponsor. Tezuka was very conscious of the fact that he was trailblazing the way for the Japanese television animation industry, and as such was adamant that production costs needed to be aligned with other live-action television programs if it was to be sustainable. However, this meant that Tezuka and his team had to develop three key techniques and strategies.

A good story can save poor animation, where good animation cannot save a poor story.”

Tezuka’s first strategy was to rely heavily on high-quality story concepts (luckily something he had in spades). He understood that a good story can save poor animation, where good animation cannot save a poor story. The second was to use a form of limited animation – animating only what was absolutely necessary. Whereas animation for feature films used between 24 and 29 frames of animation per second to give it a smooth unbroken flow, Mushi Productions were forced to use as few as 10 frames per second on occasion. To compensate for this Tezuka stressed an economy of motion. Done well, this can be used to demonstrate both a subtlety of emotion (a tightening of an eye or lip for example) as well as frantic action. The third was construct action sequences in a multi-functional way and to file away every animation cell produced in a large image bank. In this way, Mushi Productions could re-use already completed animation in new ways, thereby allowing more new animated cells to be created each episode. As the stock-image bank grew, so did an increase in the overall quality of the final product.

On January 1, 1963, Astro Boy (1963-66) hit the airwaves and was an instant hit, capturing nearly 40% of the audience. It also touched off a wave of licensed (as well as unlicensed) children’s toys and other associated products – with the benefits of commercialization invested back into the show to offset the production costs. Astro Boy (1963-66) was so successful that when a buyer for the American giant, National Broadcasting Company (NBC), who was traveling in Japan at the time, saw it, he was convinced that it must have been produced by an American company. Surprised to learn it was being produced in Japan, he contacted Mushi Productions and Tezuka was soon on his way to the United States of America – his first trip abroad. He signed a deal with NBC in New York, and Astro Boy hit the American airwaves in September 1963.

Not to be forgotten, throughout the time period he was setting up Mushi Productions and creating Japan’s first weekly, animated television show, Tezuka also continued to work on his manga. A notable addition to his regular staple became a science-fiction based series called SF Fancy Free (1963-64), which let him express his creativity in a very personal and unrestricted way that he didn’t feel he could do in his usual long-form story manga.

In 1964, Tezuka had the chance to meet one of his boyhood idols. While traveling to the 1964 New York’s World’s Fair as a special correspondent to the Sankei Shinbun, Tezuka had the opportunity for a very quick meeting with Walt Disney. Although it lasted for scarcely a minute, it was something he’d cherish for the rest of his life. Disney told Tezuka that he knew about Astro Boy (1963-66) and that he’d hoped he could do something similar in the future – a statement that had Tezuka brimming with pride and joy. What’s more, Walt Disney was not the only one to be impressed by Tezuka’s achievements. In early 1965 he received a letter from the famed film director, Stanley Kubrick, inviting him to join his production crew as a visual set designer. Kubrick has seen Astro Boy (1963-66) and been impressed by it enough to offer Tezuka the opportunity to help design the look of Kubrick’s upcoming film, 2001. Although Tezuka was flattered and incredibly interested, it would mean taking a year off work and moving to London for the duration – something he felt he couldn’t do at the time – so he turned Kubrick down.

His decision was understandable, as the mid-1960’s were a period of huge growth for Mushi Productions. The early days of a “close-knit family” had given way to a staff of between 400 to 500 people. Along with the animation projects, Mushi also began to publish Mighty Atom Club, built a further two studio buildings, and converted a vacant elementary school into a makeshift fourth.